Frontal Lobe Epilepsy

1. Introduction: frontal lobe epilepsy is an epileptic focus originated from any part of the frontal lobe. In general, most of them have the following clinical features [1-2]:

1. Motor symptoms are prominent (often with significant tonic or gestural motor behavior), and the seizure form is quite stereotypies.

2. The seizures are frequent (sometimes several times a day), each time is short (usually less than 30 seconds), and the onset and end of the seizures are often sudden.

3. Seizures are more common at night or during sleep.

4. Consciousness can be preserved during epileptic seizures, and slight or no confusion after seizures.

5. The aura of frontal lobe seizures is usually manifested as head discomfort or generalized diffuse paresthesias, often lacking clear positioning and lateralization cues.

6. Secondary generalized tonic-clonic seizures are more common.

2. Frontal lobe anatomy [1, 3-4]:

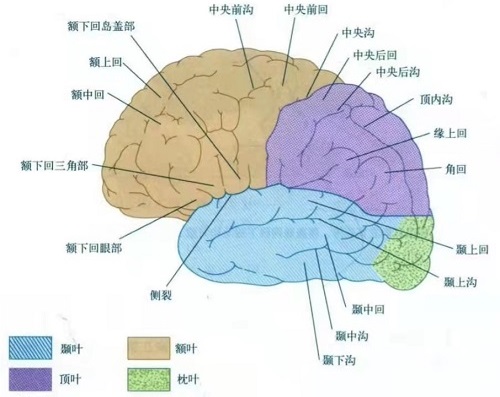

1. Morphological anatomy:

The frontal lobe occupies about the anterior 1/3 of the surface of the brain and is located above the Sylvian fissure and anterior to the central sulcus. According to morphology, it can be divided into:

1. Lateral: The posterior boundary is the central sulcus, and the lower boundary is the Sylvian fissure. There is an anterior central sulcus parallel to it in front of the central sulcus, and the precentral gyrus is between the two grooves. In front of the precentral gyrus, there are the superior frontal sulcus and the inferior frontal sulcus from top to bottom, which divide the rest of the lateral surface of the frontal lobe into the superior frontal gyrus, the middle frontal gyrus and the inferior frontal gyrus.

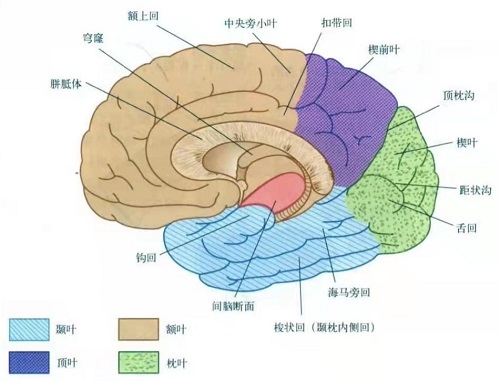

2. Medial: It is separated from the cingulate gyrus by the cingulate groove (the anterior cingulate gyrus is sometimes also considered part of the medial frontal lobe), and the posterior boundary is bounded by the line connecting the upper end of the central groove down to the cingulate groove.

3. Bottom: also known as frontal orbital surface. The medial side of the olfactory sulcus is called the straight gyrus and the lateral side is called the orbital gyrus.

2. Functional anatomy:

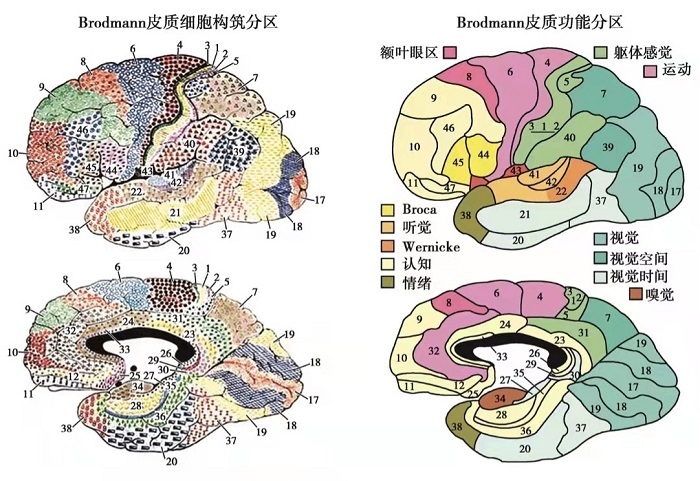

The main functions of the frontal lobe are related to mental, language and voluntary movements. It can be divided by function (the division is slightly different in different literatures. Here the frontopolar and orbitofrontal cortex are separated from the prefrontal cortex, where BA stands for Brodmann Division):

1. Primary Motor Cortex: Corresponds to area BA4 and controls the voluntary movements of the contralateral half of the body. Seizures in this area may present as focal clonic, sometimes tonic posturing, or cortical myoclonus [13].

2. Premotor Cortex: Mainly corresponds to the lateral part of the BA6 area, and plays a role in planning movement, in guidance of movement, in understanding the actions of others, and in using abstract rules to perform specific tasks. The frontal opercular is mainly located in the lower part of BA6, which belongs to the motor expression area of the head and face, and is adjacent to the Broca area, and the deep part is the insula. Frontal opercular seizures are often manifested as speech cessation, facial rigidity or convulsions, massive salivation or simple motor symptoms in the upper limbs, which may be accompanied by complex gustatory hallucinations and illusions, as well as apnea or other autonomic symptoms, scalp EEG epileptiform discharges are mainly located in the middle temporal region [1].

3. Supplementary Motor Area (SMA): mainly corresponds to the medial side of BA6 area and a small part of the lateral side, which can be subdivided into the front 1/3 of the SMA front area (pre-SMA) and the rear 2/3 SMA proper. The SMA proper has the properties of executing movements, and the pre-SMA area plays an important role in the planning and initiation of movements. Electrical stimulation of the SMA proper can cause slow tonic contractions of the proximal limbs and trunk, usually both lower limbs respond at the same time, or only the ipsilateral limb (the same upper limb or lower limb) moves, and the head and eyes can be deflected to the opposite side , there may be sensory symptoms such as tingling in the contralateral limb or both lower limbs and head. Electrical stimulation of the pre-SMA can produce inhibition of intentional movements [5-6]. The seizure in this area may first manifest as a sense of uncontrollability of the limbs, and then rapidly develop bilateral asymmetrical tonic postures, which may be manifested as fencing-like posture, M2e posture, "4" like posture etc., with speech repetition or speech termination, and consciousness can be retained, seizures spread to the anterior frontal labe may evolve into hyperkinetic, or rapid secondary to generalized tonic-clonic seizures. Because the SMA is primarily located in the medial frontal lobe, interictal and ictal discharges often occur in the midline and can spread to both hemispheres or are not recorded on scalp EEG [1-2].

4. Prefrontal Cortex, which can be further subdivided into:

1) Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex: It is mainly composed of part of the BA8 area (including the frontal eye field, which is the lower part of the BA8 area, about the rear of the middle frontal gyrus, it can make both eyes move in the same direction), BA9 area, BA46 area. The seizures can be manifested as obsessive-compulsive deflection of the head and eyes to the opposite side of the lesion, followed by generalized tonic-clonic seizures or hyperkinetic symptoms, but there are often some tonic or dystonic components in complex movements, resulting in uncoordinated movements. Interictal and ictal EEG discharges can be seen mainly in the frontal and central regions, and sometimes it can be difficult to record on the scalp EEG when the lesion or the initial range of seizure or the lesion is small and located at the bottom of the sulcus [1].

2) Ventrolateral Prefrontal Cortex: It is mainly composed of Broca area (BA44 area, BA45 area, also called the motor center for speech, located in the posterior part of the inferior frontal gyrus of the dominant hemisphere) and BA47 area. A seizure occurring in Broca's area can suddenly result in aphasia or dysphasia in a patient who is otherwise awake and responsive.

3) Medial Prefrontal Cortex: It is mainly composed of BA25 area and anterior cingulate gyrus (BA32, BA24 and BA33, there is also a certain correlation in the regulation of advanced functions such as attention allocation, emotional response, decision making and autonomic nervous system)[7-11]. The seizure onset of the anterior cingulate gyrus may first manifest as mood and affective changes and autonomic symptoms, such as fear, flushing, and heart rate changes, followed by agitational hyperkinetic symptoms, often accompanied by shouting. Because the anterior cingulate gyrus is located deep inside the medial hemisphere, abnormal discharges are often not recorded on scalp EEG[1].

5. Frontal Pole: belongs to the frontmost part of the prefrontal cortex, mainly composed of BA10 area, involved in working memory, episodic memory, multiple-task coordination and making some decisions[7]. There may be forced thoughts and behavior during frontal pole seizures. There are sometimes dialeptic seizures (so-called "frontal absences"), forward-rushing movements of the head and trunk, and sometimes axial tonic seizures[1].

6. Orbitofrontal Cortex (OFC): plays a certain role in emotion, taste, olfaction and decision-making[12], mainly composed of BA47/12, BA11, BA13, BA14 and BA10 area. Orbitofrontal seizures may initially present with olfactory hallucinations and illusions, autonomic symptoms, and affective symptoms, followed by complex motor symptoms, sometimes resembling automatisms, including repetitive upper or lower extremity fluid movements. Epileptiform discharges are often difficult to record on scalp EEG, or there may be slow waves or spikes and slow waves dominated by bilateral frontal poles [1].

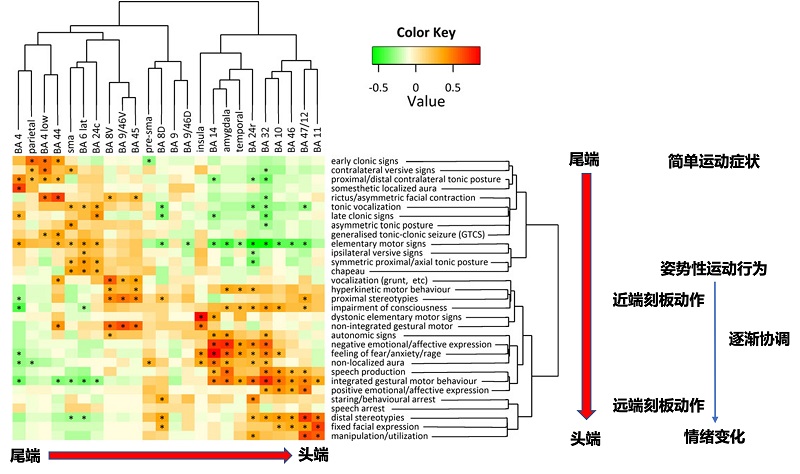

3. Relationship between clinical semiology and localization (refer to the article published in Epilepsy by Francesca bonini et al in 2014 [14]):

Overall characteristics: the closer to the front end of the frontal lobe, the more prominent the emotional changes, and the closer to the end of the frontal lobe, the closer to elementary motor signs; the more anterior the seizure organization, the more likely was the occurrence of integrated behavior; distal stereotypies were associated with the most anterior prefrontal localizations, whereas proximal stereotypies occurred in more posterior prefrontal regions.

Clinical semiology can be roughly divided into the following 4 groups:

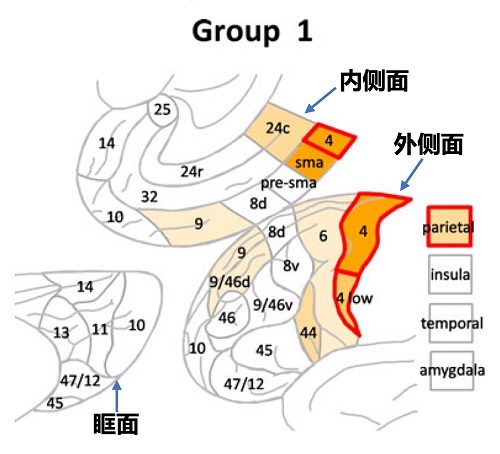

Group 1: Early clonic signs, Elementary motor signs, Proximal/distal contralateral tonic posture, Somesthetic localized aura, Contralateral versive signs, Asymmetric tonic posture, Tonic vocalization, Secondary generalized tonic–clonic seizure, Rictus/asymmetric facial contraction.

Characteristics: Predominantly one or more of the above elementary motor signs, absence of gestural motor behavior and emotional features. It mainly affects the BA4 area, but can also involvement of the premotor area and parietal cortex. Ictal discharge could involve both medial and lateral premotor regions at onset, or propagate from lateral to medial aspect.

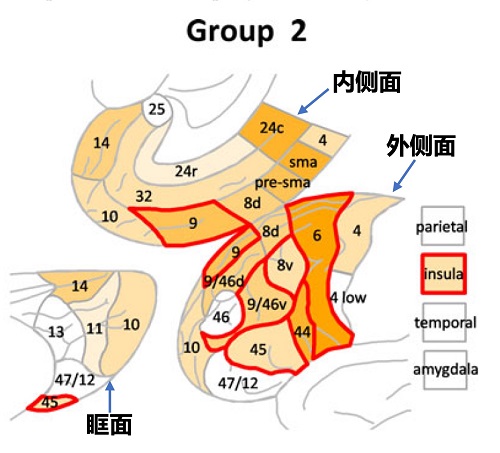

Group 2: Symmetric proximal/axial tonic posture, Nonintegrated gestural motor, Chapeau, Nonlocalized aura, Elementary motor signs, Vocalization (grunt, etc.).

Characteristics: Predominantly co-occurrence of elementary motor signs (typically symmetric axial tonic posture and facial contraction such as “chapeau de gendarme”) and nonintegrated gestural motor behavior (which may include proximal stereotypies and could have a hyperkinetic character or not), In addition, nonlocalized aura and more complex nonverbal vocalization were also frequently present, whereas integrated gestural motor behavior, distal stereotypies, early clonic signs, and fixed facial expression never occurred. It can involve the premotor area and the lateral prefrontal cortex at the same time, and can also involve the insula. The ictal discharge can involve both the medial and lateral aspect at onset. The more frequent propagation pattern was from lateral to medial regions. However, ictal discharge originating in SMA could propagate to lateral premotor regions.

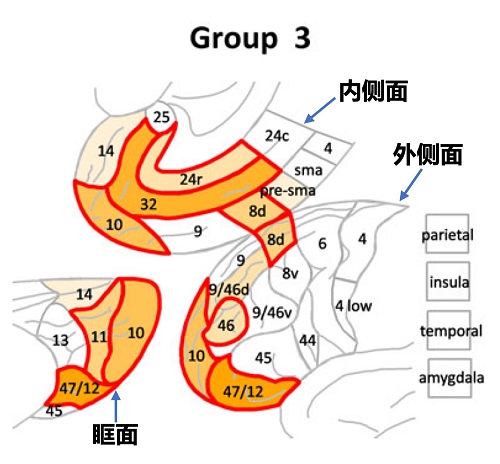

Group 3: Distal stereotypies, Fixed facial expression, Integrated gestural motor behavior, Manipulation/utilization, Positive emotional/affective expression, Proximal stereotypies, Impairment of consciousness, Speech production.

Characteristics: Mainly manifested as integrated gestural motor behavior with distal stereotypies, fixed facial expressions or alternatively, positive emotional expression, proximal stereotypies, and speech production. In addition, the absence of any elementary motor sign was a significant characteristic of these patients. It mainly involves the rostral prefrontal ventrolateral regions (BA 47/12, BA 10, BA 11, BA 46) and the rostral cingulate gyrus (BA 32 and rostral BA 24).

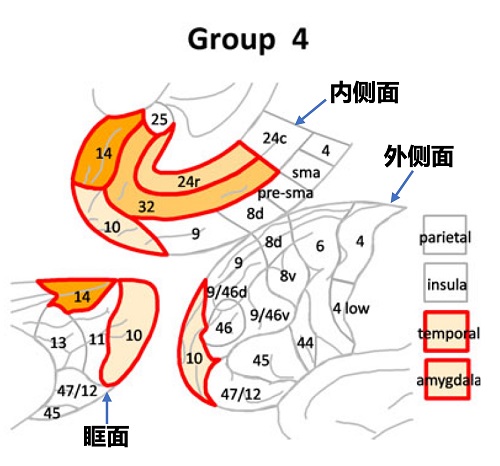

Group 4: Negative emotional/affective expression, feeling of fear/anxiety/anger, Speech production, Integrated gestural motor behavior, Autonomic signs, Nonlocalized aura, Hyperkinetic motor behavior, Impairment of consciousness.

Characteristics: Mainly presenting with integrated gestural behavior of fear, sometimes hyperkinetic, with attempt to fight or to escape, frightened facial expression, sometimes screaming or swearing, and autonomic signs. In addition, the patient did not show any elementary motor signs. Mainly involved regions corresponded to the orbital and medial-prefrontal network (BA 14, BA 32 and rostral BA 24, BA 10) with propagation to amygdala and anterior temporal regions, but not propagation to lateral frontal cortex.

References

- 刘晓燕. 临床脑电图学. 第2版. 北京 : 人民卫生出版社, 2017.

- Panayiotopoulos. 癫痫综合征及临床治疗. 北京 : 人民卫生出版社, 2012.

- 沃克斯曼. 临床神经解剖学. 南京 : 江苏凤凰科学技术出版社, 2019.

- 贾建平. 神经病学. 北京 : 人民卫生出版社, 2019.

- Lim SH, Dinner DS, Pillay PK et al. Functional anatomy of the human supplementary sensorimotor area: results of extraopera- tive electrical stimulation. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1994; 91: 179-193.

- 王玉平. 癫痫术前评估脑电图图谱. 北京 : 人民卫生出版社, 2021.

- Gilbert, S.J., et al., Functional specialization within rostral prefrontal cortex (area 10): a meta-analysis. J Cogn Neurosci, 2006. 18(6): p. 932-48.

- Pardo, J.V., et al., The anterior cingulate cortex mediates processing selection in the Stroop attentional conflict paradigm. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1990. 87(1): p. 256-9.

- Gianaros, P.J., et al., Anterior cingulate activity correlates with blood pressure during stress. Psychophysiology, 2005. 42(6): p. 627-35.

- Bush, G., P. Luu, and M.I. Posner, Cognitive and emotional influences in anterior cingulate cortex. Trends Cogn Sci, 2000. 4(6): p. 215-222.

- Bush, G., et al., Dorsal anterior cingulate cortex: a role in reward-based decision making. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2002. 99(1): p. 523-8.

- Rolls, E.T., The functions of the orbitofrontal cortex. Brain Cogn, 2004. 55(1): p. 11-29.

- Aileen McGonigal and Patrick Chauvel. Frontal Lobe Epilepsy: Seizure Semiology and Presurgical Evaluation[J]. Practical Neurology, 2004, 4(5):260-273.

- Bonini, F., et al., Frontal lobe seizures: from clinical semiology to localization. Epilepsia, 2014. 55(2): p. 264-77.

English

English  简体中文

简体中文