2025 International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) Classification of Seizures

一. The 2025 version of the Classification of Epileptic Seizures has the following major changes compared to the 2017 version:

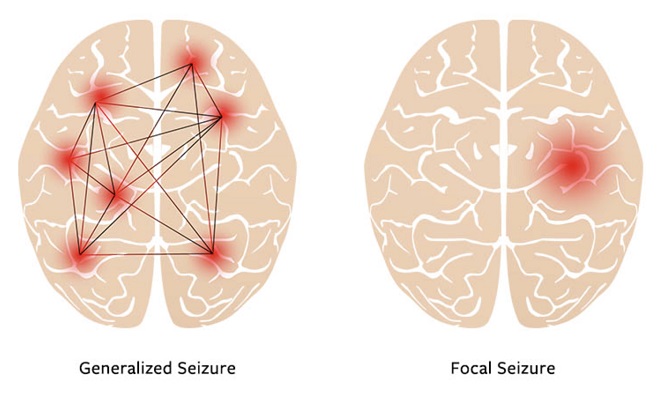

1. The term "onset" has been removed from the names of main seizure classes: compelling evidence suggests that generalized seizures may also have focal onset.

Definition of Focal Seizures:

Focal seizures are defined as originating within networks limited to one hemisphere. They may be discretely localized or more widely distributed and may originate in cortical or subcortical structures (eg, hypothalamic hamartomas). For each seizure type, ictal onset is consistent from one seizure to another, with preferential propagation patterns that may involve the contralateral hemisphere. In some cases, however, there is more than one network, and more than one seizure type, but each individual seizure type has a consistent site of onset. This also applies to independently occurring focal seizures in both hemispheres (e.g., bilateral mesial temporal lobe epilepsy or Self-limited epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes).

Definition of Generalized Seizures:

Generalized seizures are defined as originating at some point within, and rapidly engaging, bilaterally distributed networks, which can include cortical and subcortical structures, but not the entire cortex. Although seizure onset may occasionally appear localized, the localization and lateralization can vary across individual episodes. Their clinical manifestations may sometimes appear asymmetric.

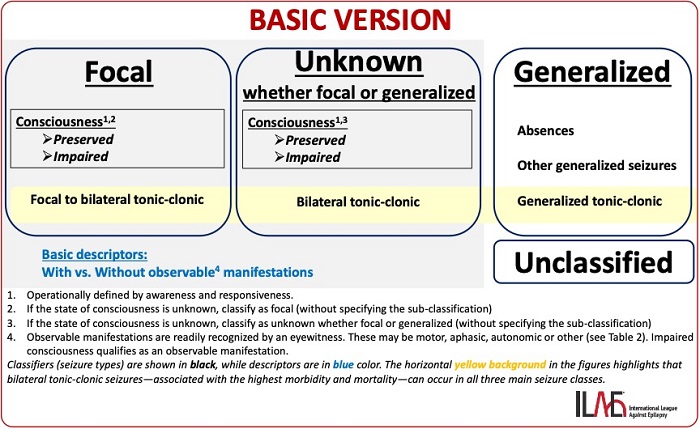

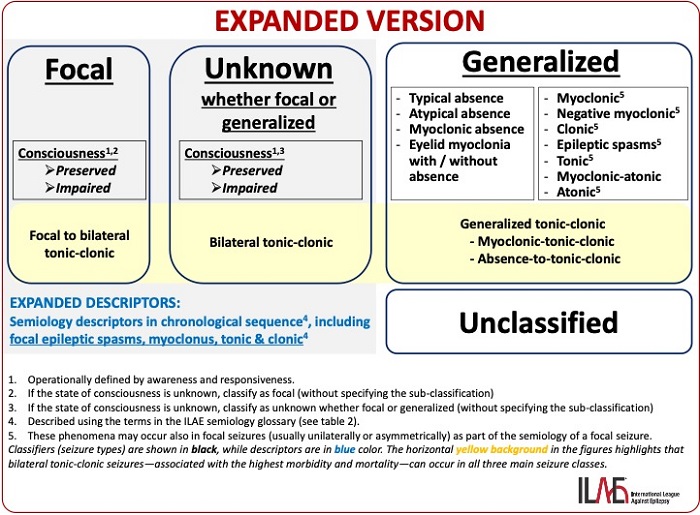

2. A distinction is made between classifiers and descriptors, based on taxonomic rule.

Classifiers reflect biological classes (conceptual justification) and directly impact clinical management (utilitarian justification). They include the main seizure classes (focal, unknown whether focal or generalized, generalized, and unclassified), the specific seizure types (21 defined seizure types), and levels of consciousness (preserved and impaired consciousness).

Descriptors represent key seizures characteristics and are primarily used in focal or unknown whether focal or generalized seizures. They are divided into a basic version and an extended version. In the basic version, seizures are classified based on the presence or absence of observable manifestations. In the extended version, seizures are described according to the chronological sequence of semiology, providing clues for lateralization and localization of the epileptogenic zone, which is of particular importance in presurgical evaluation.

3. Consciousness is used as a classifier instead of awareness, with consciousness operationally defined by awareness and responsiveness.

Consciousness can be broadly understood as the ability to respond to verbal and motor tasks (as a marker of responsiveness) and the ability to recall (as a marker of awareness) during a seizure. Assessment of consciousness level is required in focal or unknown whether focal or generalized seizures, as generalized seizures are assumed to involve impaired consciousness by default.

4. In the basic version of descriptors, the motor vs. nonmotor dichotomy is replaced by observable vs. nonobservable manifestations. This change was made because seizures previously classified as non-motor—such as typical absence seizures—often present observable motor phenomena such as discrete automatisms, head retropulsion, and eye blinks, and atypical absences may involve atonic phenomena. Notably, motor manifestations are characteristic features of specific absence seizure types, such as eyelid myoclonia with absence and myoclonic absences.

5. In the extended version of descriptors, seizures are described according to the chronological sequence of seizure semiology, rather than relying solely on the initial symptom. This approach is particularly suited for cases with long-term video-EEG monitoring, as it allows for describing the seizure evolution. It plays an important role in characterizing the seizure propagation network and in studies of clinical–anatomical correlations, making it especially valuable for presurgical evaluation.

6. Epileptic negative myoclonus is recognized as a seizure type.

7. The 2025 classification of seizures includes four main classes and 21 seizure types, representing a significant simplification compared to the 2017 version, which included 63 seizure types. When epileptic spasm, myoclonic, epileptic negative myoclonus, clonic, tonic, tonic–clonic, atonic, and myoclonic–atonic manifestations occur as generalized seizures, they are classified as distinct seizure types. However, when these manifestations occur in focal seizures—typically presenting unilaterally or asymmetrically—they are considered part of the focal seizure semiology.

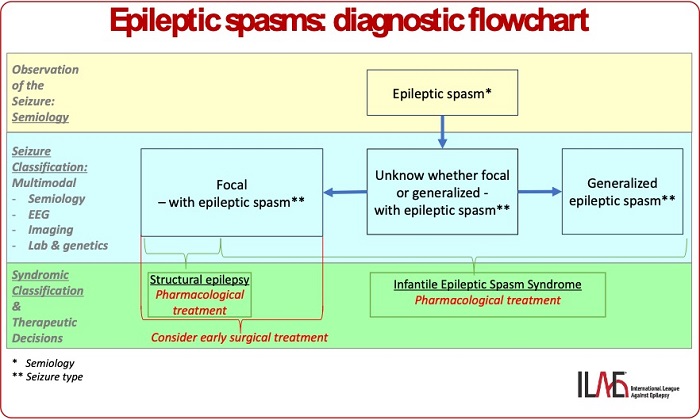

8. Added a diagnostic flowchart for epileptic spasms.

二. Taxonomic hierarchy of epileptic seizure classification:

1、Focal (F)

1.1. Focal preserved consciousness seizure (FPC)

1.2. Focal impaired consciousness seizure (FIC)

1.3. Focal-to-bilateral tonic-clonic seizure (FBTC)

Descriptors

• Basic:

o With observable manifestations

o Without observable manifestations

• Expanded:

o Semiology descriptors in chronological sequence:

Semiology (glossarya*) + Somatotopic modifiers

2、Unknown whether focal or generalized (U)

2.1. Unknown whether focal or generalized - preserved consciousness seizure (PC)

2.2. Unknown whether focal or generalized - impaired consciousness seizure (IC)

2.3. Unknown whether focal or generalized - bilateral tonic-clonic seizure (BTC)

Descriptors

• Basic:

o With observable manifestations

o Without observable manifestations

• Expanded:

o Semiology descriptors in chronological sequence:

Semiology (glossarya*) + Somatotopic modifiers

3、Generalized (G)

3.1. Absence seizures (AS)

3.1.1. Typical absence seizure (TA)

3.1.2. Atypical absence seizure (AA)

3.1.3. Myoclonic absence seizure (MA)

3.1.4. Eyelid myoclonia with / without absence (EMA)

3.2. Generalized tonic-clonic seizure (GTC)

3.2.1. Myoclonic tonic-clonic seizure

3.2.2. Absence-to-tonic-clonic seizure

3.3. Other generalized seizures**

3.3.1. Generalized myoclonic seizure (GM)

3.3.2. Generalized clonic seizure (GC)

3.3.3. Generalized negative myoclonic seizure (GNM)

3.3.4. Generalized epileptic spasms (GES)

3.3.5. Generalized tonic seizure (GT)

3.3.6. Generalized atonic seizure (GA)

3.3.7. Generalized myoclonic-atonic seizure (GMA)

4、Unclassified

Note: Classifiers are shown in black, whereas descriptors are in blue. Main classes are indicated in bold font; seizure types are underlined.

*See Table 2 for semiological features.

**This is a grouping term, not a defined concept.

FIGURE 1 Basic version of the updated seizure classification.

FIGURE 2 Expanded version of the updated seizure classification.

TABLE2 Descriptors for focal seizures and for seizures unknown whether focal or generalized.

Somatotopic modifiers

Side (left, right, bilateral–symmetric, bilateral–asymmetric) + body part

Semiological features

1. Elementary motor phenomenaa

• Akinetic: characterized by the inability to perform voluntary movements with preserved postural tone and awareness. Akinetic motor signs are often associated with dystonic phenomena, but it can also evolve to include progressive loss of muscle tone. Akinetic signs are likely to occur during seizures that involve “negative motor” areas (i.e., mesial premotor cortex and inferior frontal gyrus).

• Astatic (a.k.a. ”epileptic drop attack”): refers to a sudden loss of maintaining an erect posture. This leads to falling without specificity for identifying the underlying mechanism (i.e., from atonic, myoclonic, or tonic seizures).

• Atonic: refers to a sudden loss or decrease in muscle tone involving the head, trunk, jaw, and limbs. Atonic seizures typically last 1-2 seconds and can result in a loss of postural tone, without tonic, clonic, or myoclonic manifestations. Atonic seizures occur in both generalized and focal epilepsies. Their occurrence in focal seizures suggest motor and premotor cortex involvement.

• Dystonia: associated with a seizure (ictal dystonia) consists of sustained contractions involving both agonist and antagonist muscles. This produces athetoid or twisting movements which, when prolonged, may produce unnatural postures of an arm or leg. The dystonic posture can manifest as flexion or extension and be proximal or distal, frequently with a rotatory component. In the context of patients with temporal lobe epilepsy, unilateral ictal dystonia of the upper limb almost always lateralizes to the hemisphere contralateral to the seizure onset zone.

• Ictal paresis: characterized by weakness or paralysis of a part of one’s body or hemibody. Ictal paresis must be differentiated from ictal akinesia, ictal immobile limb in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy, and postictal Todd’s paresis. A proper diagnosis therefore necessitates video-EEG to test the patient and confirm the ictal origin of the motor deficit. Ictal paresis is almost always contralateral to the seizure onset zone and is likely to be produced by seizures that occur in close vicinity to the primary motor cortex.

• Clonic: refers to relatively rhythmic jerking movements. In focal motor seizures, unilateral clonic manifestations have a high lateralizing value to the contralateral hemisphere (approximately 90%) and strongly reflect involvement of the motor cortex.

• Myoclonic: a sudden, brief (<100-msec) involuntary, single or multiple contraction(s) of muscle(s) or muscle groups of variable topography. The term clonic (synonym rhythmic myoclonic) should be preferred to account for myoclonic jerks that are regular and repetitive, at a low frequency that is typically 0.2-5 Hz.

• Epileptic negative myoclonus: used to describe a brief interruption of muscle tone (<500 msec), like atonic seizures. It can occur in a heterogeneous group of epilepsy syndromes disorders, ranging from Atypical Childhood Epilepsy With Centrotemporal Spikes, to focal epilepsies involving lesions of the mesial frontal structures (as in neuronal migration disorders), and Myoclonic Encephalopathy In Non-progressive Disorders or Progressive Myoclonus Epilepsies.

• Myoclonic–atonic: associated with a myoclonic jerk followed by an atonic motor component. This seizure type is the hallmark semiology in patients with Doose Syndrome.

• Tonic: consists of a sudden posture involving increased tone resulting in stiffness or tense posture due to sustained muscular contraction that usually causes an extension. They may be symmetrical or asymmetrical and frequently lead to falls. Unilateral tonic seizures lateralize to the contralateral hemisphere in approximately 90% of patients with focal epilepsy.

Chapeau de gendarme (a.k.a. ictal pouting): consists of a “symmetrical and sustained (>3-sec) lowering of labial commissures with contraction of the chin, mimicking an expression of fear, disgust, or menace”. This produces a facial expression that is recognized by a turned down mouth that appears as an inverted smile. When it occurs early during seizures, it has a strong localizing value to the frontal lobe especially the anterior prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortices.

Fencing posture: a motor sign with tonic extension at the elbow and elevation of one arm and strongly lateralizes to the contralateral hemisphere. In addition, there is associated ipsilateral flexion of the elbow in the ipsilateral upper limb and elevation at the shoulder to approximate the posture held during fencing. This typically occurs late in the course of a seizure and suggests seizure onset in the hemisphere opposite to the elevated arm..

M2e: beginning with flexion of the elbow to about 90 degrees and followed by an abduction of the shoulder to approximately 90 degrees, associated with external rotation with or without head turning towards the affected arm. The initial description emphasized that a M2e motor posture should be used as a descriptor only if the contralateral arm is initially uninvolved or becomes involved in tonic activity later during the seizure. This sign suggests seizure onset in the hemisphere contralateral to the affected arm.

• Tonic-clonic: consisting of a tonic phase followed by a clonic phase. In focal seizures, the bilateral tonic-clonic phases are typically preceded by other focal semiologies (FBTC). However, when they occur at night and are unwitnessed or before its treatment, it may be impossible to identify the presence of focal signs or symptoms.

Figure-of-four: may occur at the onset of the tonic phase prior to the clonic phase in patients with FBTC seizures. This semiology consists of unilateral tonic extension of one arm and tonic flexion of the contralateral arm. This sign is considered to have a good lateralizing significance with the extended arm occurring contralateral to the hemi- sphere involved in seizure onset. The sequence of motor signs is important and can be complex, with tonic extension of one limb first, followed by the figure-of-4 sign pointing to the other hemisphere. In this situation, it is the first manifestation of arm extension that prevails to lateralize the seizure onset zone.

Asymmetric clonic ending: refers to the terminal expression involving clonic jerks following a focal-to-bilateral-tonic seizure. When convulsive seizures terminate asymmetrically with unilateral clonic jerks that persist on one side of the body, this has good lateralizing significance for seizure onset. The last unilateral clonic activity that persists occurs ipsilateral to the hemisphere of seizure onset.

• Epileptic spasm: a seizure comprised of sudden flexion, extension, or mixed extension-flex- ion. Spasms involve predominantly the proximal head, appendicular and truncal muscles and are more sustained than brief clonic and myoclonic movements, but not as sustained as tonic posturing which may last 0.5-2 seconds. Typically, spasms consist of a series of episodes with abduction and extension of both arms. Subtle forms of spasms, with minimal/discrete manifestations may occur, including head nodding, grimacing, smiling, or chin movement. Epileptic spasms usually occur in clusters, often upon awakening. When unilateral or asymmetric, they point towards a lateralized onset in the contralateral hemisphere.

• Gyratory: refer to seizures where the patient rotates around their long body axis. This phenomenon may be initiated by a versive head movement in the same direction and may culminate in a focal-to- bilateral tonic-clonic (FBTC) seizure. During focal seizures, the direction of the rotation lateralizes the seizure onset zone to the contralateral hemisphere when head version initiates the gyration. However, in gyratory seizures without preceding forced head version, the lateralizing value is unclear.

• Versive: must be used only to describe an unnatural, forced and sustained movement of the eyes, head, trunk or whole body to one side. Small lateral saccadic and clonic features can be superimposed during version. Ictal version can be seen with focal seizures arising from any location. Isolated version involving the eyes likely involves the contralateral frontal eye fields. However, when initial visual illusions/hallucinations are congruent with ocular version, this suggests seizures arise from a contralateral occipital lobe origin. Head version strongly lateralizes to the contralateral hemisphere when it is associated with neck extension and occurs in the first 10 seconds of a FBTC seizure. In the situation where two successive head versions occur prior to a FBTC seizure, it is the movement immediately preceding the tonic-clonic phase that prevails as the lateralizing sign.

• Head orientation: Non-versive turning of the head and eyes (relatively natural, non-forced, and voluntary movement) is a frequent, but not specific sign when determining lateralization and localization. When it occurs early in temporal lobe seizures, it is often ipsilateral to the focus.

• Eye deviation: Includes both non-forced orientation and forced versive movements, often accompanied by head movements. Forced eye deviation has strong lateralizing significance and typically suggests seizure onset in the contralateral hemisphere.

• Eye blinking: consists of a series of repetitive tonic contraction of the eyelids during a seizure. This occurs without any other facial muscle contraction. Its lateralizing value, when unilateral, suggests an ipsilateral epileptogenic hemisphere. Unilateral ictal eye blinking is believed to result from cortical blink inhibition of the contralateral eye, due to seizures in the frontotemporal region.

• Epileptic nystagmus: sometimes described as oculo-clonic jerks, is a rapid, repetitive movement of the eyeballs probably caused by the epileptiform activity involved in activation of the cortical region governing saccadic or pursuit eye movements. It is binocular in most cases and may be preceded or accompanied by simple visual hallucinations. It is often associated with rotation of the head and eyes that is often in the same direction as the fast phase of nystagmoid eye movement which is most prominent. Epileptic nystagmus is mainly seen during seizures of occipital lobe origin, and the fast phase is most often contralateral to the site of seizure onset.

2. Complex motor phenomenaa

• Automatisms: used to account for an irrepressible, discrete or excessive and repetitive single motor activity that often resembles a voluntary behavior. They may appear to occur with a semi purposeful act such as disrobing and manipulating objects or without the appearance of a purposeful behavior such as body rocking. Patients seldom retain awareness when exhibiting automatisms yet they will typically be unaware of them.

○ Gestural automatisms—distal: are rhythmic repetitive movements of the hands and occasionally also of the feet (e.g., tapping, crumbling, fumbling, grasping, finger snapping, exploratory movements, manipulating movements). In the context of temporal lobe epilepsy, unilateral manual automatisms lateralize to the ipsilateral hemisphere mainly when associated with a contralateral hand dystonia.

○ Gestural automatisms—genital: directed to involve the genital region. These complex motor behaviors may appear with a sexual appearance including fondling, grabbing, scratching among other beha- viors. They are often unilateral and associated with manual automatisms. They are frequently ipsilateral to the hemisphere involving the seizure onset zone.

○ Gestural automatisms—proximal: described when rhythmic repetitive movements of the proximal extremities occur (e.g., pedaling, kicking, wing flapping, body rolling, rocking, crawling, and copulatory movements). These often result in highly visible movements with high amplitudes and fast speeds. They coexist as part of hyperkinetic behavior and their localizing significance is unclear, though often are associated with seizure onset in the frontal lobe involving the anterior cingulate or orbito-frontal cortex, though may also be seen in insular, temporal and parietal lobe seizures.

○ Ictal grasping: defined as a uni- or bi-manual forced prehensile movement often preceded by reaching. It is either directed towards the patient’s body or surrounding one’s personal space. It rarely occurs as the main clinical component of the seizure and is frequently part of hyperkinetic behaviors. Ictal grasping is often contralateral, but it is without consistent lateralizing value.

○ Mimic automatisms (gelastic, dacrystic): refer to a stereotyped mimicry or behavior that resembles the usual way one expresses oneself to reflect an affect that is not accompanied by the corresponding emotion. The most frequent types of mimetic automatisms are laughing (gelastic) and crying (dacrystic, quiritarian) behaviors which, when isolated and occurring in clusters, should make one consider the possibility of hypothalamic localization (i.e., hamartoma). Other localizations also exist, mainly involving the frontal and temporal lobes. A tendency for ictal laugh, though without overt laughter (hence not qualifying as a gelastic seizure), has been described in patients with small hypothalamic hamartomas. Other mimic automatisms are rarely identified but include the expression of negative (e.g., biting, fear, sadness)and positive (i.e., kissing) emotional valences, or musical automatisms (e.g., humming and whistling) .

○ Oroalimentary automatisms: including chewing, lip smacking, lip pursuing, licking, and swallowing resemble normal routine behaviors and are frequently encountered in patients with temporal lobe seizures, especially those arising from the mesial structures. The appearance of preserved awareness during such automatisms is more likely to occur during temporal lobe seizures that arise from the non-dominant hemisphere for language.

○ Verbal automatisms: reflect the iterative and stereotyped production of intelligible words or sentences. Verbal automatisms are frequently seen in patients with temporal lobe seizure.

○ Vocal automatisms: refers to single or repetitive sounds (e.g., grunts, shrieks, moaning etc.) that do not have the linguistic qualities of language like verbal automatisms and are unaccompanied by apnea, tonic, clonic, or tonic-clonic motor manifestations. Ictal vocalization by itself has no localizing significance but it occurs more frequently in dominant temporal and frontal lobe seizures.

• Hyperkinetic behavior: shows an excessive amount and speed of motor movement. There is an increased rate and acceleration of ictal motor movement and the appearance or inappropriate rapid performance of a movement. Hyperkinetic behaviors are often produced by seizures arising from the frontal lobe, although extrafrontal origins are also possible.

3. Sensory phenomenab

• Auditory: Elementary auditory symptoms are uni- or bilateral buzzing, drumming, ringing, whistling sounds. They can be narrow- (single tone) or broad-band (noise). Auditory illusions refer to an alteration of unimodal auditory perceptions which can consist of a modification of intensity (more or less intense) of tone (higher or lower pitched) or distance (closer or farther away). Elementary auditory phenomena point to the primary auditory cortex in the superior part of the temporal lobe (Heschl’s gyrus).

• Visual: composed of either positive or negative phenomena during seizures. Positive elementary phenomena are comprised of static or moving unformed flashes of lights, “spots”, or “blobs”. They may be white, black or include color, remain localized or be non-localized within a visual field (i.e., quadrantic, hemi-field, or occupy the whole visual field) . Negative elementary phenomena correspond to transient amaurosis of the entire visual field or scotoma when it is confined to part of it (quadrantanopia, hemianopia, tunnel vision). Intermediary visual hallucinations are more complex. They may appear as geometric forms (i.e., stars, circles, triangles, squares, diamond) and possess a slightly different sub-lobar localizing value. Visual illusions comprise a great variety of visual phenomena affecting an object or its visual background. This spans from visual blurring to an alteration of size (micropsia/macropsia), color (dyschromatopsia), shape (metamorphopsia), distance or movement (kinetopsia), and number (diplopia, polyopia). Palinopsia refers to the persistence or recurrence of a visual object when the stimulus is no longer present. Elaborate visual phenomena refers to unimodal visual hallucinations with detailed and meaningful implications such as faces, people, body parts, animals, and images of scenes that occur without a clear mnemonic or affective component, as well as unimodal visual hallucinations associated with elaborate negative phenomena which is dominated by the presence of prosopagnosia. Visual phenomena are a key feature of occipital seizures.

• Gustatory: represent abnormal paroxysmal tastes within the mouth or in the throat. These are usually unpleasant, and may be reported as salty, metallic, bitter, sour, acidic or indescribable. They have been reported in seizures from peri-rolandic, insular and opercular regions.

• Olfactory: defined as a paroxysmal unexplained sense of smell. These are usually, but not always, unpleasant and can be neutral or even pleasant experiences. Olfactory hallucinations can be described as an odor of burning, sulfur, alcohol, gas, garbage, barbecue, flowers, among other descrip- tions, or be indescribable. Olfactory symptoms have been reported mostly in seizures arising from medial temporal structures involving a range of etiologies including tumor and hippocampal sclerosis.

• Somatosensory: may be described as tingling, numbness, electrical, shock-like sensation, pain, or sense of movement. Somatosensory auras typically occur in patients with parietal lobe seizures and represent the most frequently described aura arising from this region. They are mostly unilateral sensations, contralateral to the epilepto- genic zone but may also occasionally be bilateral or even ipsilateral to seizure onset. Painful somatosensory auras are described by patients as acute and intense pain (burning sensation, pricking ache, throbbing pain or muscle tearing sensation), affecting the body. Painful auras most often lateralizes the hemisphere involved at seizure onset. Painful sensory auras may secondarily produce the motor behavioral manifestations of pain, involving a corresponding facial expression, verbal complaints including shouting and crying, movements in an effort to avoid a perceived stimulus, or autonomic changes such as facial pallor or flushing. Painful auras strongly suggest involvement of the posterior insula and parietal operculum. Painful auras typically are contralateral to seizure onset but they may be bilateral or even ipsilateral when the painful sensation centers in the face and trunk.Ictal headache should be strictly differentiated from a painful somatosensory aura because they are thought to reflect a vascular mechanism rather than an electrophysiologic disturbance involving a localized cortical somatosensory area responsible for pain. It does not have localizing value when it is encountered, but is more likely to be ipsilateral to the seizure onset when it occurs in patients with temporal lobe seizures.

• Vestibular/dizziness: defined as a sensation of spinning or motion involving the body, with or without a sensation of unsteadiness. This illusion of motion might be described as rotatory symptoms in the up-down or left-right plane, a sense of movement, floating, or undefinable sense of body motion. In practice, it can be difficult to delineate the semiology of vestibular symptoms and differentiate them from the general non-specific term of dizziness that are vague and ill-defined sensations. Vestibular auras are rare, yet important symptoms reported with the highest prevalence in patients with parietal lobe seizures.

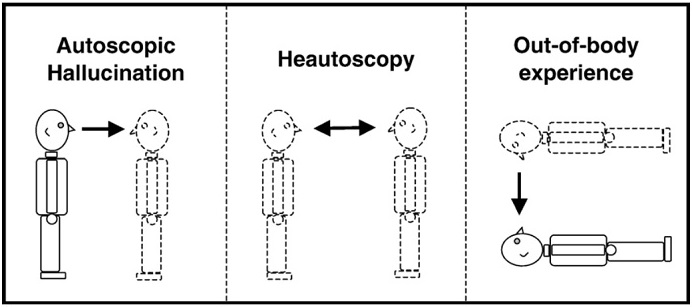

• Body-perception illusion: somatagnosic auras result from a disturbance of unimodal somatosensory (proprioceptive and tactile) self-representation of the body. Autoscopic symptoms result from a disturbance of multimodal self- integration of body including visual perception of one’s body, either from an internal perspective of the body (autoscopic hallucination), or from an external perspective (out-of-body-experience), or when patients cannot decide whether one’s self is located inside the physical properties of the body or reside outside of it (heautoscopic hallucination). Somatagnosic auras comprise non-visual, illusions of the body such that one feels disconnected, dislocated or a sense of movement, experiences phantom limbs or reduplication, or deformity involving a body part. These are rare but suggest a non-dominant (right) temporo-parietal junction as the site of seizure involvement. Autoscopic hallucinations are rare, tend to be more often perceived in the contralateral visual field and suggest right (non-dominant) medial occipitoparietal cortex (pre-cuneus and occipito-parietal sulcus) involvement. An out-of-body-experience typically points to the non-dominant lateral parietal lobe, but also may occur with seizures arising from the dominant temporoparietal region.

• Depersonalization: defined as the detachment from oneself, either the mind or body. In addition, this may involve being a detached external observer of oneself during a seizure. There is a phenomenological overlap between autoscopic phenomena (out-of- body experience) and depersonalization. Depersonalization needs to be differentiated from derealization, which refers to the altered perception of one’s surroundings that is experienced as a sensation of unreality.

4. Cognitive and language phenomenac

• Aphasia: is the inability to comprehend or formulate language during focal seizures. Ictal aphasia can be manifest as Wernicke’s (receptive), Broca’s (expressive), or global (mixed) aphasia. It may be difficult to differentiate aphasia in patients with impaired consciousness, unless behavioral testing specifically addresses specific components of language. Inability to name objects has been referred to as ictal anomia. Ictal aphasia suggests involvement of the speech and language areas in the dominant hemisphere. However, in a large study involving ictal aphasia in patients with focal epilepsies, this semiological presentation had limited localizing value within the dominant hemisphere and was most commonly seen in patients with seizures originating from the parieto-occipital regions, and even with seizures spreading from the non-dominant to dominant language areas of the brain.

• Dysmnesia

○ Amnesia: implies that the patient cannot recall events during the seizure, or at least a part of the seizure.

○ Déjà vu/déjà vécu/jamais vu/dreamy state/reminiscence: Déjà vu/déjà vécu refer to the sensation of having previously experienced the present situation. Déjà vu typically involves a visually dominated sense of familiarity, while déjà vécu refers to a more immersive, multimodal recollection-like experience, often with richer contextual detail. Jamais vu as the feeling one has experienced the situation for the first time, despite having been in the situation before. Dreamy state refers to a vivid memory-like hallucinations. These symptoms suggest a symptomatogenic zone in the temporal lobe, primarily the mesial structures (amygdala and hippocampus) and the sub-hippocampal structures (rhinal cortices). The temporal neocortex might also play a significant role in producing these phenomena.

• Forced thinking: defined as involving intrusive thoughts, ideas, or words in people and should be differentiated from both a dreamy state and complex sensory hallucinations. According to some authors, the definition also includes an overwhelming impulse to perform a certain act. The lateralizing and localizing value of ictal forced thinking remains uncertain. Most likely, the symptomatogenic zone resides in the dominant frontal lobe.

• Confusion/disorientation: Confusion defined as unable to function and think with customary speed, clarity. Disorientations in the different domains are classified as self-referenced (incorrect self-localization) or nonself-referenced (incorrect localization or knowledge of other places, events, and people).

• Other focal cognitive deficits:

Anosognosia: refers to a condition in which the patient is unaware of their own deficits (such as hemiplegia), typically associated with involvement of the non-dominant hemisphere.

Apraxia: applied to a state in which a clear-minded patient with no weakness, ataxia, or other extrapyramidal derangement, and no defect of the primary modes of sensation, loses the ability to execute highly complex and previously learned skills and gestures.

Neglect: It can manifest as hemispatial neglect.

5. Autonomic phenomenac

• Cardiovascular

○ Ictal tachycardia: the most common ictal autonomic sign. Ictal tachycardia often preceded EEG changes and occurred more frequently in patients with temporal rather than extratemporal seizures.

○ Ictal bradycardia: much less frequent than ictal tachycardia. This is usually observed in patients with temporal lobe seizures. Bradycardia may occur in the context of respiratory depression.

○ Ictal asystole: much less frequent than ictal tachycardia. This is usually observed in patients with temporal lobe seizures. Falls and myoclonus were observed with prolonged ictal asystole (mean: 14.8±7 s) .

• Cutaneous/thermoregulatory

○ Flushing: resulting from skin hyperperfusion, has been reported as part of the autonomic manifestations of seizures.

○ Piloerection: defined as erection of the hairs of the skin due to contraction of the tiny arrectores pilorum muscles that elevates the hair follicles above the rest of the skin, moving the hair vertically and appearing to “stand on end” (gooseflesh or goosebumps). Piloerection is usually associated with other autonomic symptoms, such as sweating, flushing, and shivering. There is a strong association with temporal lobe epilepsies including the insula and amygdala. Recent reports reveal a strong representation of autoimmune encephalitis and gliomas as a cause of seizures associated with piloerection.

○ Sweating: It usually occurs in association with other symptoms including shivering, abdominal pain, headache and vertigo or with the sensation of generalized coldness.

• Epigastric: epigastric aura, especially when accompanied by oral and manual automatisms, is highly suggestive of a seizure origin in the temporal lobe.

• Gastrointestinal

○ Sialorrhea/Hypersalivation: Ictal hypersalivation appears to suggest a mesial temporal localization. Invasive EEG recordings in isolated cases have implicated the perisylvian frontal operculumand the insula.

○ Spitting: has been implicated in several studies as lateralizing to the non-dominant hemisphere. However, involvement of the left temporal lobe has also been reported in some cases. In one case evaluated with invasive EEG, although the seizure onset zone was located in the left mesial temporal lobe, ictal spitting coincided with the propagation of ictal discharges to the right temporal lobe, implicating the latter as the symptomatogenic zone. Furthermore, direct electrical stimulation studies during invasive EEG monitoring have identified the entorhinal cortex as a region involved in ictal spitting.

○ Nausea/Vomiting: These symptoms are relatively common in Self-limited Epilepsy With Autonomic Features and are partially associated with involvement of the temporal lobe (particularly the mesial structures) and the insular cortex.

○ Flatulence: It suggests temporal and insular involvement during seizure propagation.

○ Borborygmi: the rumbling sounds of gas moving in the intestines.

○ Polydipsia: May present as an intense urge to drink water during epileptic seizures and is thought to be associated with involvement of the temporal lobe.

• Pupillary

○ Miosis: a rare autonomic sign that has been described as a part of generalized photosensitive epilepsies and in patients with focal epilepsies involving the temporal, parietal and occipital lobe. The localizing and lateralizing value for miosis in patients with epilepsy is uncertain.

○ Mydriasis: a common sign seen bilaterally when it is associated with seizures in patients with either GTCS or FBTC seizures. This is due to widespread activation of the cortical and subcortical structures of the brain that influence the sympathetic nervous system.

• Respiratory

○ Hypoventilation: May lead to ictal hypoxemia during seizures.

○ Apnea: Central apnea may precede seizure onset recorded on scalp EEG in more than a half of cases, and rarely persists into the postictal period. Oxygen desaturation less than 90% significantly correlated with temporal lobe localization at seizure onset, right hemispheric seizure lateralization, and contralateral hemispheric propagation.

○ Choking: due to acute laryngospasm as an isolated event associated with nocturnal seizures may rarely represent an ictal manifestation. Ictal choking observed during stimulation studies has implicated the frontal operculum and anterior insula. In patients with insular seizures, the semiology typically begins in patients who are fully consciousness and experience a sensation of laryngeal constriction that is often associated with unpleasant paresthesia, affecting large cutaneous territories.

○ Hyperventilation: more commonly observed in older children, females, individuals with frontal lobe seizures, and seizures with right-sided lateralization. In children, frontal lobe epilepsy—often originating from the frontal pole or orbitofrontal regions—is more frequently associated with hyperventilation. In adult patients, when hyperventilation occurs during seizures, it is more likely to be related to mesial temporal lobe epilepsy.

• Urinary

○ Incontinence: This can occur in various types of epileptic seizures but is most commonly seen during tonic-clonic seizures. During a seizure, urinary incontinence may result from a loss of muscle control or from hyperexcitability of neurons in the brain regions responsible for bladder regulation.

○ Urinary sensations/Urinary urge: Characterized by an intense urge to urinate during the ictal phase, this symptom is associated with involvement of the temporal lobe and insular cortex in the non-dominant hemisphere.

6. Affective (emotional) phenomenac

• Anger: occur in patients with seizures associated with a strong feeling of annoyance, displeasure, or hostility. Stereotyped evolution during each event, and the presence of other features and semiologies are often present. Focal seizures with anger localize to the mesial temporal networks, especially the amygdala.

• Anxiety: during a focal aware seizure may produce a feeling of worry, nervousness, or unease typically about an imminent event, or something with an uncertain outcome. The best examples of ictal anxiety are generally considered to reflect involvement of the amygdala.

• Fear: An intense, unpleasant emotion triggered by the perception of danger. In most patients with ictal fear, seizures originate from the mesial temporal lobe, typically associated with involvement of the amygdala.

• Sadness: A state of feeling or expressing sorrow, unhappiness, or melancholy, which rarely occurs as an isolated ictal symptom. Focal seizures associated with sadness originating from hypothalamic hamartomas may be accompanied by lacrimation, sad facial expressions, and sobbing.

• Guilt: an affective symptom involving an emotional feeling of having done wrong or failed in an obligation.

• Ecstatic/Bliss: Characterized by an intense sense of happiness and pleasure, heightened bodily comfort, unusually vivid self-awareness or external perception, and a “surreal” state of consciousness (such as a feeling of unity with the universe). These experiences may involve the insular cortex and anterior cingulate gyrus.

• Mirth: Laughter accompanied by a genuine emotional experience of joy, which may be associated with involvement of the basal temporal structures.

• Mystic: Transcendent experiences with religious or spiritual significance, such as a sense of unity with God or the apprehension of truth beyond rational understanding, possibly associated with involvement of the temporal lobe.

• Sexual: These may manifest as sexual desire, arousal, or orgasmic aura. In most cases, the origin is in the right cerebral hemisphere. Sexual auras typically arise from the mesial temporal structures, though some studies have indicated that they may also originate from the anterior cingulate cortex and the frontal lobe.

7. Indescribable aurab

• Postictal phenomena

○ Unresponsiveness: the most common phenomenon Recovery from postictal unresponsiveness may take seconds to minutes.

○ Paresis (Todd's paresis): Occurs after focal motor seizures or focal to bilateral tonic-clonic seizures (FBTC), and can last from several minutes to several hours. It lateralizes to the contralateral hemisphere. Most commonly seen in seizures originating from the frontal lobe, although cases with origins in other regions have also been reported.

○ Blindness (hemianopsia or amaurosis): following seizures, loss of vision may occur on one side of the visual field (hemianopsia) or both sides (amaurosis). The duration typically lasts from seconds to hours. It has been reported in two-thirds of patients with Childhood Occipital Epilepsy (Gastaut Type) . Postictal blindness points to involvement of the visual cortex and has been described in patients with occipital and temporal lobe seizures. Ictal homonymous hemianopsia later- alizes to the contralateral hemisphere.

○ Language dysfunction: comprises Broca’s, Wernicke’s, and global aphasia; anomia; paraphasia; and errors in repetition and writing. The duration is typically from seconds to minutes. Most postictal language disturbances occur in patients with focal seizures involving either onset in or propagation to the dominant temporal lobe.

○ Nose-wiping: More frequently observed in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. In these patients, nose-wiping most often occurs on the same side as the hemisphere of seizure onset.

○ Headache: postictal headache often manifests with severe migraine-like features. In temporal lobe epilepsy, postictal headache was found to be ipsilateral to the site of seizure onset in 90% of cases. However, no significant lateraliza- tion value was found in patients with frontal lobe epilepsies.

○ Palinacousis: involving preservation of an external auditory stimulus or retained fragment of a previously heard sentence may occur after seizure cessation.

○ Autonomic signs: comprise a wide range of pheno- mena including ictal tachycardia, bradycardia, arrhythmia, hypersalivation, coughing, apnea, tachypnea, changes in blood pressure, hyperthermia, and neurogenic edema. Postictal coughing occurs in both temporal and extratemporal lobe epilepsies and may only be indicative of a temporal lobe seizure onset when seizures are represented by a stereotypical semiology. Respira- tory depression and cardiac dysfunction, occurring after a GTCS (including FBTC seizures), are critical factors in SUDEP.

○ Psychiatric signs: These include delirium, psychosis, catatonia, impaired cognition and amnesia. Delirium, changes in perception (hallucinations), thoughts (incoherence, delusions) and catatonia may last for hours to days. Postictal psychosis can develop after a “lucid phase” when the patient recovers from initial postictal confusion, only to reappear six hours to a week later. Postictal depressive and anxiety symptoms may occur for more than 24 hours and within five days following a seizure.

○ Confusion: Refers to a period following a seizure (lasting from several minutes to several days), during which the patient is unable to think clearly. It is typically accompanied by impaired attention/concentration, short-term memory deficits, reduced verbal output and decreased social interaction, as well as other specific cognitive impairments related to the epileptogenic region.

Note: If phenomena not listed above occur during the seizure, they are added in free text.

Awareness and responsiveness define consciousness and hence are classifiers.

All items in this table are defined in the International League Against Epilepsy glossary of semiology.

aObservable manifestations.

bNot observable manifestations.

cPossibly observable manifestations.

Example:

1. A young woman awakens to find her 20-year-old boyfriend having a seizure in bed. The onset is not witnessed, but she is able to describe bilateral stiffening followed by bilateral “shaking.” EEG and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings are normal.

Classification of epileptic seizures: Unknown whether focal or generalized - bilateral tonic-clonic seizure (BTC)

In an alternate scenario of the previous case, the EEG shows a clear right parietal slowwave focus. The MRI shows a right parietal region of cortical dysplasia. Classification of epileptic seizures: Focal-to-bilateral tonic-clonic seizure (FBTC)

2. A 25-year-old woman describes seizures beginning with 30s of an intense feeling that “familiar music is playing.” She can hear other people talking but afterward realizes that she could not determine what they were saying. Eyewitnesses report that the patient does not respond to external stimuli during the seizure, neither verbal nor tactile (touching the patient). After an episode, she is mildly confused and has to “reorient herself.”

Classification of epileptic seizures: Focal impaired consciousness seizure (FIC)

Descriptors:auditory aura ➔ receptive aphasia ➔ impaired responsiveness ➔ postictal confusion.

3. A 22-year-old man has seizures during which he remains fully aware, with the “hair on my arms standing on edge” and a feeling of being flushed.

Classification of epileptic seizures: Focal preserved consciousness seizure (FPC)

Descriptors:With observable manifestations: piloerection + flushing.

4. A 13-year-old with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy has seizures beginning with a few jerks, followed by stiffening of all limbs and then rhythmic jerking of all limbs.

Classification of epileptic seizures: Myoclonic tonic-clonic seizure

5. A 3-month-old boy has clusters of short sei- zures with flexion in the neck and hips, and abduction in the shoulders of short duration (up to 2 s). The patient has 3–15 clusters per day. The child was encephalopathic, without developmental progression. Seizures were resistant to multiple antiseizure medications, including adrenocorticotropic hormone. Repeated MRI was unrevealing. Video-EEG showed epileptic spasms associated with a generalized suppression on EEG.

Classification of epileptic seizures: Generalized epileptic spasms

6. A 14-month-old girl has sudden extension of both arms and flexion of the trunk for approx- imately 2 s. These seizures repeat in clusters. EEG shows hypsarrhythmia with bilateral spikes, most prominent over the left parietal region. MRI shows left parietal cortical dysplasia.

Classification of epileptic seizures: Focal seizure with epileptic spasms (brief version: focal epileptic spasms)

7. During long-term video-EEG monitoring, a 28-year-old female patient experiences an ascending sensation from the stomach and then starts chewing and manipulating nearby ob- jects using the right hand. The patient can recall what happens during these episodes and is able to respond.

Classification of epileptic seizures: Focal preserved consciousness seizure

Descriptors: epigastric aura ➔ oroalimentary automatisms + gestural automatismsm + preserved awareness and responsiveness.

8. An 8-year-old boy reports episodes starting with seeing colored dots and stripes on the left side. The patient cannot recall what happened after that, but eyewitnesses report that the patient does not respond to verbal and tactile stimuli, turns the head to the left, becomes stiff, and then has jerks in all limbs.

Classification of epileptic seizures: Focal-to-bilateral tonic-clonic seizure (FBTC)

Descriptors: elementary visual aura on the left side ➔ versive to left + loss of awareness and responsiveness ➔ bilateral tonic–clonic.

9. A 33-year-old, right-handed man experienced febrile seizures in infancy. Habitual, unpro- voked seizures started at the age of 15years and were accompanied by a feeling of abdominal discomfort followed by loss of awareness. His wife reported that approximately once per month he displays episodes of lip smacking, fumbling hand movements, and occasional right-hand posturing.

Classification of epileptic seizures: Focal impaired consciousness seizure (FIC)

Descriptors: epigastric aura ➔ impaired awareness ➔ oroalimentary automatisms + gestural automatisms + dystonic posturing in the right hand.

References:

- Updated classification of epileptic seizures: Position paper of the International League Against Epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2025 Apr 23.

- Seizure semiology: ILAE glossary of terms and their significance. Epileptic Disord. 2022 Jun 1;24(3):447-495.

- Focal electroclinical features in generalized tonic-clonic seizures: Decision flowchart for a diagnostic challenge. Epilepsia. 2024 Mar;65(3):725-738.

- Out-of-body experience, heautoscopy, and autoscopic hallucination of neurological origin Implications for neurocognitive mechanisms of corporeal awareness and self-consciousness. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2005 Dec 1;50(1):184-99.

- Protracted Ictal Confusion in Elderly Patients. Arch Neurol. 2006 Apr;63(4):529-32.

- Orientation and disorientation: lessons from patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2014 Dec:41:149-57.

- Anosognosia during Wada testing. Neurology. 1992 Apr;42(4):925-7.

- Negative motor seizure arising from the negative motor area: is it ictal apraxia? Epilepsia. 2009 Sep;50(9):2072-84.

- Severe hemispatial neglect as a manifestation of seizures and nonconvulsive status epilepticus: utility of prolonged EEG monitoring. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2015 Apr;32(2):e4-7.

- Mirthful gelastic seizures with ictal involvement of temporobasal regions.Epileptic Disord. 2009 Mar;11(1):82-6.

English

English  简体中文

简体中文